This website contains information, links, images and videos of sexually explicit material (collectively, the 'Sexually Explicit Material'). Do NOT continue if: (i) you are not at least 18 years of age or the age of majority in each and every jurisdiction in which you will or may view the Sexually Explicit Material, whichever is higher (the 'Age of Majority'), (ii) such material offends you,. Wall Mounted Outside Mailbox Postbox Mail Post Letter Box Galvanized Grey. LOCKABLE OUTSIDE LETTERBOX LETTER POST MAIL BOX POSTBOX WITH KEYED LOCKSET.

PrimeMatik - Letter mail post box mailbox letterbox metallic gray color for wallmount 215 x 81 x 316 mm. Delivery fee from £32.75. Show product details. Length (mm) 185. Color: Dark Grey Verified Purchase The letter box arrived severely damaged with a hole punched through one side and dents and crumples on other sides. The box it was shipped in with other items was undamaged. Someone thought it was a good idea to ship the box in the condition it was in.

| Greyfriars | |

|---|---|

Greyfriars Hous | |

| Location | Puttenham, Surrey |

| Coordinates | 51°13′34″N0°38′48″W / 51.2262°N 0.6468°WCoordinates: 51°13′34″N0°38′48″W / 51.2262°N 0.6468°W |

| Built | 1896 |

| Architect | C.F.A. Voysey |

| Architectural style(s) | Arts and Crafts |

| Official name | Greyfriars |

| Designated | 13 December 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1029612 |

Location of Greyfriars House in Surrey | |

Garden Trading Charcoal Grey Letter Post Mail Box With Lock Wall Mounted. Top-rated sellerTop-rated seller.

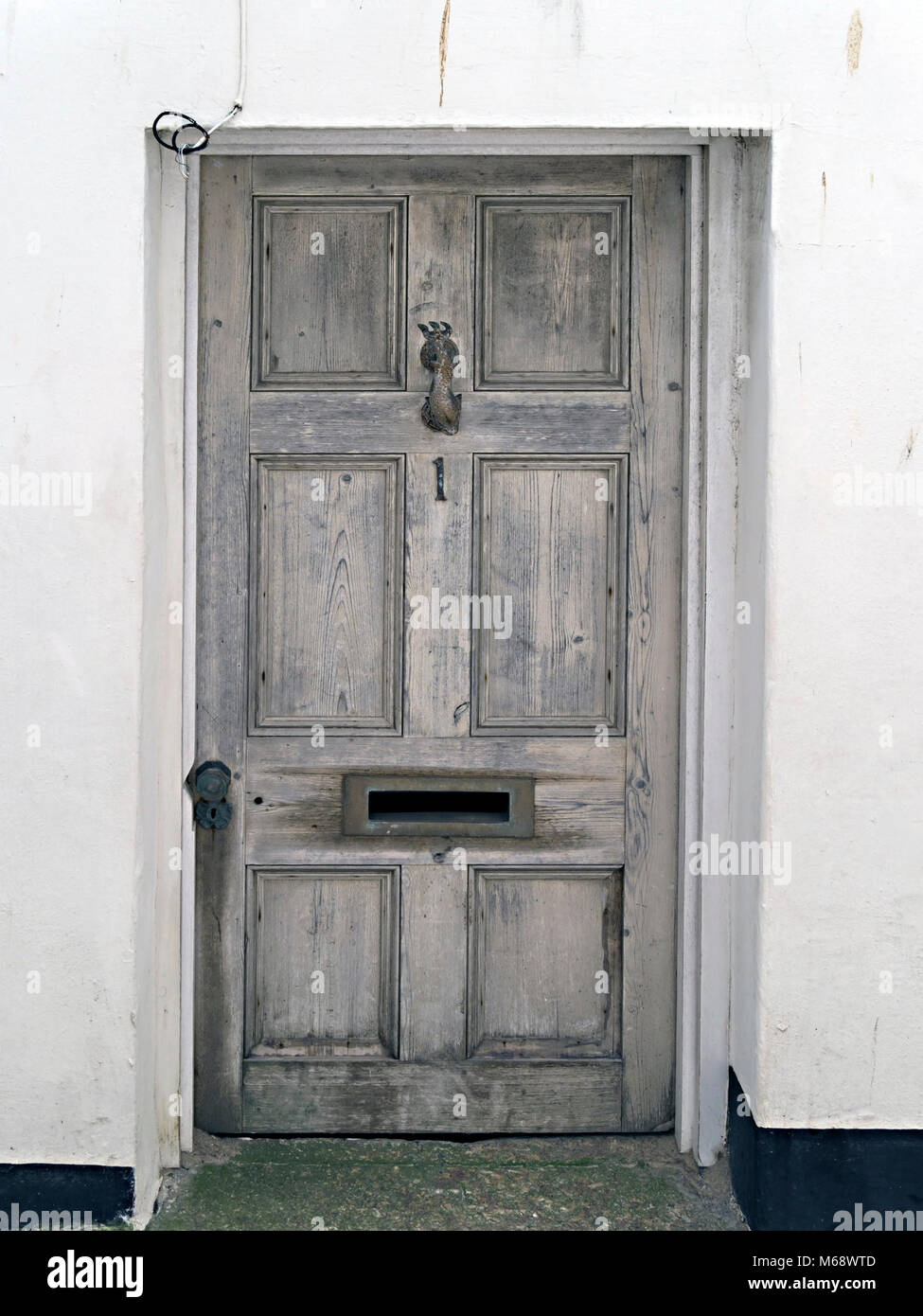

[[File:|right|thumb|300px|e]]Greyfriars is a Grade II* listed house located on the Hog's Back near the village of Puttenham, in Surrey, England. It was built in 1896 for the novelist and playwright Julian Sturgis and was designed by the arts and crafts architect C.F.A. Voysey.[1] It has been Grade II* listed on the National Heritage List for England since December 1984.[2] The house was previously known as Wancote, and was initially called Merleshanger.[3]

The house was later extended on its western end by Herbert Baker in 1913-14.[2] 20 drawings of the design and detail of Greyfriars are held in the collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Howard Gaye's watercolour of Greyfriars was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1897.[4] Voysey's distinctive heart shaped motif is on Greyfriar's letter box, hinges and door handles.[5]

The house was put up for sale with its staff cottages in 2003 for £3 million.[5]

The Sturgis family[edit]

Julian Russell Sturgis (1848-1904) who built Greyfriars House was a notable Victorian novelist, poet and musical composer. He was born in Boston, USA in 1848. His father was Russell Sturgis the famous merchant and later head of Baring Bank. He came to England at an early age. He went to Eton and later obtained his degree at the University of Oxford where he excelled in football and rowing. He later became a barrister. However his real love was writing and in 1878 he embarked on a career as a novelist. In 1883 his father died and left him a considerable fortune. He had a London residence in Knightsbridge as well as a country house.[6]

In 1883 he married Mary Maud, daughter of Colonel Marcus de la Poer Beresford and the couple had three sons. Citrix web app chrome free. In 1896 he commissioned the famous architect Charles Voysey to build Greyfriars House. It is still considered to be one of Voysey’s best designs. The famous architectural expert Nikolaus Pevsner made the following comment.

- 'Greyfriars is one of Voysey’s best houses built in 1896 for Julian Sturgis. Superb position facing just under the brow of Hog’s Back. The long, low roughcast house ties itself self-effacingly into the landscape and the pleasure to be got from walking around it is that of a continuous interchange between building and landscape without any single view that can be analysed in detail.'[7]

Being a writer Julian had several famous friends who visited him at Greyfriars House (then called Wancote). Henry James in 1904 sent a letter to Julian’s recently widowed wife mentioning his long friendship with her husband.[8] He continued to occasionally visit her at the house after Julian’s death He noted in one of his letters of 1912 to a friend that he recently went there for a weekend.[9] Julian was also a friend of Arthur Christopher Benson whom he sometimes visited and who returned his visits by coming to Greyfriars.[10]

When Julian died in 1904 his wife Mary and his son Sir Mark Beresford Russell Grant-Sturgis (1884-1949) continued to live at the house. In 1914 Mark married Rachel Montagu-Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie, daughter of the 2nd Earl of Wharncliff.[11] The wedding was widely reported in the newspapers and a photo is shown. The couple had two sons.

He was assistant private secretary to H. H. Asquith when chancellor of the exchequer (1906–8), and private secretary to him as prime minister (1908–10). He later became Assistant Under Secretary for Ireland between 1920 and 1922. During this time he wrote five volumes of diaries on the Irish uprising.[12]

In 1920 the Sturgis family put Greyfriars House on the market and it was sold to Philip Lyle App cleaner & uninstaller big sur.

Other residents[edit]

Philip Lyle who bought the house in the 1920s lived there for the next 15 years. He was a Director in the Tate & Lyle sugar refining company. In 1926 he invited the magazine “Garden Life” to the house and they wrote an article describing the property at this time.[13] He sold the house in 1936 and it was bought by Robert Heap Turner (1900-1986), the wealthy industrialist. He lived there for the next 50 years and after his death in 1986 the house was sold.

References[edit]

- ^Cole, 2015 pg. 117

- ^ abHistoric England, 'Greyfriars (1029612)', National Heritage List for England, retrieved 14 October 2017

- ^Cole, 2015 pg. 117

- ^Cole, 2015 pg. 117

- ^ abKathleen Hennessy (19 January 2003). 'Dream home: Greyfriars'. The Guardian. Retrieved 12 October 2017.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Lee, Elizabeth “Sturgis, Julian Russell, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^Pevsner, N. Nairn I et al 1971 “Surrey”, p. 267. Online reference

- ^Letters of Henry James Vol 2. Online reference

- ^Gunter, S. e. 2004 “Dearly Beloved Friends: Henry James's Letters to Younger Men”, 162. Online reference

- ^Edwardian excursions: from the diaries of A.C. Benson, 1898-1904, p. 44. Online reference

- ^The Peerage website Online reference

- ^Seedorf, M. F. “Sturgis, Sir Mark Beresford Russell Grant”, Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

- ^“Garden Life”, Vol 50, 1926. Online reference

- Cole, David. (2015) The Art and Architecture of C.F.A Voysey: English Pioneer Modernist Architect and Designer Images Publishing ISBN9781864706048

External links[edit]

For the latest classic car news, features, buyer’s guides and classifieds, sign up to the C&SC newsletter here

The fame and public profile of Alvis was still indelibly linked to private motor car production in the early ’50s.

And yet, among the stern-looking managers, directors and engineers who guided this revered firm through its tricky post-war years, there must have been many who knew its future lay firmly elsewhere.

Alvis Ltd was already well on the way to becoming a pure engineering firm (that merely built cars as a sideline) by the time its first truly new post-war model, the TA21 3-litre, appeared in 1950.

Formal, compact and unpretentious, the 3-litres were not the glamour machines that the Speed 25 and the 4.3 had been in their time.

Yet in conception and execution, these post-war cars were still very much what the pre-war customer would have expected of an Alvis: a refined car of balanced but sporty attributes that was fast, not excessively thirsty and handled well.

At a time when a prestige car had to be big to justify its existence, here was a traditional-looking saloon or drophead that was large enough to have presence and comfort, but not so big and heavy that it became an encumbrance in the city or an embarrassment on the A- and B-roads that linked our major conurbations; the first motorways were still a decade away.

Even in 1950 the 3-litre looked anachronistic with its separate wings and flat ’screen, but, with so many shoebox-like unitary construction cars emerging, most wealthy customers would have found the Alvis visually reassuring.

Gray Letter Board

With its rear-hinged ‘suicide’ doors and upright grille, the Mulliners of Birmingham-bodied four-door looked exactly the sort of well-groomed machine that the Coventry firm might have introduced some time in the early ’40s had a world war not intervened: German bombs virtually destroyed the firm’s car-making facilities early in the conflict.

The basic shape of the 3-litre saloon can be traced directly to the 1937 12/70 saloon, the pre-war antecedent of the TA14.

If Tickford’s two-door TA21 drophead coupé (from 1951) was not quite as ravishing as the Vanden Plas Short Chassis 4.3-litre Alvis of 10 years earlier, it was still a very acceptable way of reintroducing open-topped motoring to Holyhead Road’s six-cylinder customers.

The similar-looking (but pre-war in origin) TB14 had kept the name alive in the second half of the 1940s, and the 3-litre was only ever seen as a mid-term solution while a more modern, higher-volume Alvis was developed for the second half of the ’50s and beyond.

But when that now near-mythical, Alec Issigonis-designed V8 saloon (C&SC, June 2008) was axed in 1955, the fate of Alvis as a car maker was sealed.

With the remunerative distractions of its government contracts for the Leonides radial engine and Stalwart six-wheeler, the firm had to put the innovation of the pre-war years behind it for car production to continue.

Would Alvis customers have accepted the dumpy, Morris Oxford-like TA-350? Perhaps the company was right to settle for a low-volume, low-key existence, developing the 3-litre technology to a logical conclusion.

Without the investment in body tooling for the abortive V8, the main problem Alvis had – along with most other low- and mid-volume specialist makes – was continuity of body supply.

It was tied to contracts with coachbuilders who, in the case of both Mulliners and Tickford, lost their independence and could no longer supply bodies to Alvis due to new allegiances.

This was the situation that led to the demise of the TC21/100 in 1955, and with it a lull in Alvis car making while a new way of sourcing bodywork was found.

Alvis could never get its volumes high enough to acquire the economies of scale that would put its cars on a competitive price footing (at least not without compromising its well-deserved reputation for careful, high-quality construction), or achieve the returns that would justify tooling up for a new model.

In many ways the TA21 and TC21 represent the last Alvis cars to sell in anything like significant quantities, with 2043 built between 1950 and ’55.

A handsome 1300 orders were taken at the 1950 Geneva show launch alone, such was the appetite for new product. But as the 1950s unfolded the demand tailed off.

First seen as the TA21 in 1950, these all-new post-war 3-litre cars fully lived up to the fine tradition for quality that Alvis had established between 1919 and 1940, reaffirming the name among the ranks of the nation’s better cars.

For his or her £1800, the buyer of a 3-litre Alvis got a well-engineered car that would serve for business and family purposes – and, if necessary, go a long time between major overhauls.

It was a practical thoroughbred that might not have been the absolute fastest in raw figures, but could cover the ground as quickly as any four-seater saloon then available.

This point was well made by the evocative advertising, conjuring images of carefree motoring under the wide vistas and traffic-free roads of Northumberland.

‘The pulsing power of your Alvis,’ stated the copy beneath a picture of a deserted and arrow-straight Roman road, ‘will speedily accept such an open invitation.’

From a firm that had pioneered front-wheel drive and synchromesh gears before WW2 and had been among the first British marques to adopt independent front suspension, the 3-litre was conservatively engineered as a long-life car with driver appeal.

Prioritising top-gear flexibility over top-end horsepower, its straight-six engine had nearly square dimensions, a rugged seven-main-bearing crankshaft and a rear-chain-driven camshaft for the overhead in-line valves.

Its twin-leading-shoe brakes were hydraulic, with a particularly generous friction area, and the centre of gravity was low down in a fully welded box-section chassis that, as well as being lighter than it looked, boasted coil-sprung independent front wheels with a solid rear axle located on long semi-elliptic leaf springs.

Supplanting the 86mph TA21 in 1953, the TC21 was an acknowledgement of the wider availability of high-octane fuels that left Alvis free to offer a higher-compression, twin-SU-carburetted version of the 3-litre engine.

The twin SUs had replaced the original single Solex quite early on, but it was only when the higher 3.77:1 axle ratio was used that the 3-litre became a true 100mph car.

Alvis viewed this as noteworthy enough to justify a change of name to TC21/100. It was also known as the ‘Grey Lady’, a title first used by the firm’s sales manager when he saw the ’53 Earls Court show car, which was painted grey with grey leather.

The historical waters are a little muddied here as to what constitutes a TC21/100 Grey Lady as opposed to a mere TC21.

What I can tell you is that only late TC21s had the chromed door frames and hidden hinges of the TC21/100s, which additionally – as a rule of thumb, but not a certainty – had the famous bonnet scoops plus wire wheels, spotlamps and side louvres.

Grey Letter Box Uk

Of the 727 TC21s and TC21/100s there were only 100 dropheads, all to the latter specification.

This royal blue Grey Lady saloon seems originally to have been ordered with the ‘plain’ bonnet and steel wheels, which illustrates the point nicely.

Subject of a five-year, body-off rebuild in the mid-’90s, it has led a quieter life than the Tickford drophead, which was sold new to Lady Courtauld and, in 1974, exported to America by its fourth owner as ‘personal baggage’ on the USS Enterprise.

It lived in San Francisco for 25 years (where Clint Eastwood graced its seats) and then followed its owner to Switzerland at the turn of the century.

After regular trips back to the UK for its annual MoT test, it was subjected to a £50,000 restoration by marque specialist Tim Walker in 2003.

Mark Elder of Bicester Heritage-based The Motor Shed was brought up on the Alvis marque by his father Malcolm, whose monthly adverts in C&SC almost always featured a ‘red triangle’-badged vehicle, the vintage 12/50s being a favourite. Mark maintains that tradition with a selection of five vintage and post-vintage thoroughbred four-cylinder cars in his current inventory alongside the two TC21/100s.

Styled in the handsome perpendicular school, the 3-litre twins have long, imposing snouts but sit quite low on a relatively wide front track.

The rubber grommets in the overriders are jacking points – handy on a car whose chassis features 19 grease points that need attention every 1000 miles.

Under the centre-hinged bonnets the engines look like generic ‘sixes’ but are also thoughtfully finished, with a cover for the spark plugs and detachable side panels to aid access.

To enter the cabin, you reverse onto the flat, shapeless front seats through the suicide-type doors that were just beginning to fall out of favour even on the more genteel English makes in the 1950s.

The atmosphere inside is that of an Edwardian headmaster’s study: comfortably finished in fine materials, but not lavish.

The drophead has a nicely contrived hood, with fully open or Coupe de Ville positions.

The saloon’s tiny back doors give access to decent rear legroom on an elevated bench that features triple armrests, the cosy feeling offered by the letterbox-type rear window further enhanced by a remotely operated sunblind.

Heaters were included and, in the saloon, ventilation is augmented by a big steel sliding sunroof, also standard.

Nearly flush to the windscreen, the plain, unfussy walnut dashboard features cream switchgear and four minor gauges flanking a 100mph speedometer.

Starting is instant on the electric choke, which on the drophead has an override switch that allows you to dispense with it almost straight away.

Virtually silent at tickover, these engines are flexible enough to make first gear all but redundant on level ground and your choice of ratio is almost irrelevant to the initial acceleration. The lack of synchromesh on first feels a backward step but is no real hardship.

The lower ratios hum tunefully in unison with the soft growl of a straight-six that on 100bhp pushes this not notably windcheating saloon to a guaranteed 100mph, putting the TC21/100 in an elite group of ton-up true four-seaters.

You need the leverage supplied by the large sprung steering wheel for manoeuvring at low speeds.

Its fixed centre boss depicts the famous red triangle in the claws of an eagle, and you can see how 3-litre owners must have enjoyed that ‘mastery of the road’ feeling, looking down the long bonnet as this distinguished but not ostentatious car put the miles behind it in the tired, monochrome Britain of the early ’50s.

Under way, the drophead feels slightly the sharper of the two, picking up speed eagerly in third and top, but the saloon is not far behind.

Both are superbly flexible and sweet in top gear and you rarely need to drop below third, which would, theoretically, extend to 85mph.

The pedals are sited close together and the throttle is a roller type, giving sensitive control over an engine that will wind out smoothly to its 4000rpm power peak. (The drophead has an aftermarket rev-counter fitted.)

The brakes have long travel in both and the clutch action is on the heavy side of moderate, but it is no chore to stir the short gearlever that pokes assertively out of the carpeted central tunnel.

Its hefty but precise action is a microcosm of the semi-vintage overall character of the Alvis, rewarding decisive, well-timed movements with mechanical feel.

Grey Letterbox Wall Mounted

While its mass-produced rivals were tending towards lower-effort controls – with the dialled-in safety valve of strongly understeer-prone handling to cater to a broader set of skill levels – the TC21/100 still assumed a level of interest in the task in hand.

Above walking pace the heft disappears from the steering and such understeer as there is can be easily countered by boosting the 3-litre through the corner.

So, instead of running wide on tortured rubber like the grocer’s Super Snipe or the bank manager’s Rover, the Alvis feels tidy and biddable, with accurate steering that doesn’t load up but castors smoothly back through the hands and doesn’t feel low-geared.

You expect – and get – some roll in tighter, slower corners, but the general agility is beyond reasonable expectations and not achieved at the expense of the ride: while it’s no magic carpet, it remains level and composed.

Driving this pair, it’s easy to see why Alvis ownership has always bred a special kind of loyalty.

In the case of the 3-litre, this meant a diverse group of personalities that embraced everyone from double-amputee war hero Douglas Bader to singer Carmen Miranda (she of the fruit-bearing headgear) via Hitchcock’s favourite composer, Bernard Herrmann, who was a particularly keen Alvis man.

They appreciated the reassuringly expensive 3-litre for its reliability, its brisk turn of speed and the solid value its purchase represented in a fast-changing world of superficially plusher, flashier machines with less enduring appeal.

Smaller than a Standard Steel Bentley and much less frumpy than an Armstrong Siddeley or a Daimler, the Alvis TC21/100 was a car for the driver who drove himself and took a certain amount of pride in doing so.

It still is.

Images: John Bradshaw

Grey Letterbox Tiles

Thanks to Mark Elder, The Motor Shed Ltd

Factfile

Alvis TC21/100

- Sold/number built 1953-’55/727 (all TC21s)

- Construction steel chassis, ash frame, steel/aluminium body

- Engine all-iron, ohv 2993cc straight-six, twin SU carburettors

- Max power 100bhp @ 4000rpm

- Max torque 152Ib ft @ 2500rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

- Suspension: front independent, by wishbones, coil springs rear live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs; telescopic dampers f/r

- Steering Burman recirculating ball

- Brakes hydraulic drums

- Length 15ft 2in (4623mm)

- Width 5ft 6in (1676mm)

- Height 5ft 2½in (1588mm)

- Wheelbase 9ft 3½in (2832mm)

- Weight 3500Ib (1588kg)

- Mpg 20

- 0-60mph 15 secs

- Top speed 100mph

- Price new £1821

- Price now £25-60,000*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

Grey Letter Board

READ MORE Two finger scroll not working in excel for mac.

Comments are closed.